DEPICTING OBESITY IN BLACK AMERICA

Overview

Obesity is a major health problem for millions of Americans. Dietary patterns, physical inactivity, medication use, and other exposures contribute to the prevalence of obesity in America. In an article, "Is Fat the New Normal?" Sherry Rauh likens obesity among Americans to tallness among basketball players.

"If you're tall enough to stand out in a crowd, you're probably aware of your tallness - maybe even self-conscious about it. But imagine that you're in a room full of basketball players. Suddenly, you don't seem so tall anymore. Your above average height feels normal." - S. Rauh

Rauh suggests that if we equate "normal" with average, it's not a stretch to say that in America, it's normal to be obese. The average or "normal" American adult's BMI is 28.6, which signifies overweight. The new normality of excess weight makes it very difficult for Americans to recognize what obesity looks like. This poses a serious concern in populations such as African Americans where obesity is highly prevalent.

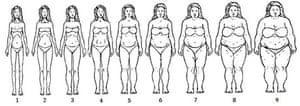

Rush University MC Study

A study conducted by researchers from the Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, recruited sixty-nine African American women from a low income neighborhood of Chicago and asked them to identify which of the nine women (shown below) were overweight, obese, and "too fat". The consensus was that of the nine women shown, only 8 and 9 were "too fat" (Boosely).

Implications

This simple study conveys a larger disagreement between cultural and medical definitions of "healthy" in the African American community. This disconnect poses a much larger problem considering the effect of obesity on quality of life and risk for other chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, and some types of cancer. Since these illnesses are already disproportionately prevalent in minority populations, measures must be taken to mend this disconnect and push African Americans toward health equity.

What could be done?

1. Examination of social determinants of health that contribute to African American obesity. Determinants such as income, neighborhood, educational attainment, food advertising, and access to parks, grocery stores, and green space all play a critical role in the overall health of a community. African American communities face significant disparities in these determinants. Therefore, to help African Americans live healthier lives, these disparities must be eradicated. This will require strategic programs, policies, and neighborhood revitalization efforts that increase the availability and access to healthy food and safe space to be physically active in African American communities.

2. Development of culturally relevant healthy living and weight loss programs tailored to meet the unique needs of African Americans. To enhance cultural relevance and appeal to African Americans, these programs should solicit input from population members, use culturally relevant intervention content, incorporate population media figures, utilize culturally relevant forms of physical activity, and address specific population linked barriers to activity (Conn). For example, Steps to Soulful Living, a weight loss intervention for African American women, successfully reduced participants' weight by 8 - 15 pounds using these strategies (Karanja).

3. Use of nontraditional partners to increase health education in minority and low income communities. Instead of relying on traditional health education providers such as hospitals and clinics, providers should use nontraditional sources such as churches, community centers, sorority and fraternities, and barbershops/salons to conduct successful lifestyle interventions in settings that are both familiar and comfortable in the Black community (Kennedy et al).

Sources:

Boseley, Sarah. "Do You Know What Fat Looks Like?" Editorial. Obesity: The Shape We're In Blog. The Guardian, 10 Sept. 2014. Web. 29 Sept. 2015.

Conn, Vicki S., Keith Chan, JoAnne Banks, Todd M. Ruppar, and Jane Scharff. "Cultural Relevance of Physical Activity Intervention Research with Underrepresented Populations." Int Q Community Health Education34.4 (2013): 391-414. NCBI. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Web. 30 Sept. 2015.

Karanja, N., VJ Stevens, JF Hollis, and SK Kumanyika. "Steps to Soulful Living (steps): A Weight Loss Program for African-American Women." Ethnicity and Disease 12.3 (2002): 363-71. National Center for Biotechnology Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Web. 30 Sept. 2015.

Kennedy, Betty, Jamy Ard, Louis Harrison, Beverly Conish, Eugene Kennedy, Erma Levy, and Phillip Brantley. "Cultural Characteristics of African Americans: Implications for the Design of Trials That Target Behavior and Health Promotion Programs." Ethnicity and Disease 17 (2007): 548-54. Cite Seer X. Pennsylvania State University. Web. 30 Sept. 2015.

Rauh, Sherry. "Is Fat Normal in America? A Surprising Reason Why We're Gaining Weight." WebMD. WebMD, n.d. Web. 29 Sept. 2015.

The State of Obesity: Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Obesity. Rep. N.p.: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2014. Web. 30 Sept. 2015.